The Capital Stack for Multifamily Development

Forum

Capital Advisors LLC

Forum

Capital Advisors LLC

The Fed’s aggressive fight to rein in inflation by increasing interest rates to their highest levels in 16 years has broadly impacted banks, as witnessed by the Silicon Valley, Signature Bank, and First Republic bank failures, and caused stress in the capital markets resulting in a banking capital crunch not witnessed since the global financial crisis. After feasting on widespread increases in consumer deposits from the COVID-19 stimulus, banks are fighting to keep them, as short-term Treasury bond yields averaging 5.45% have provided a higher-yielding alternative to consumers, thus placing stress on bank deposits, driving up the rates that consumers require to keep their funds with banks. This has led to the further impairment of many bank balance sheets. The environment is further complicated by increasing loan maturities, which are likely to remain on bank balance sheets because takeout financing levels at today’s higher interest rates often result in insufficient proceeds to retire initially maturing loans. This forces borrowers to exercise extension options (or seek extensions, often with the need of additional equity infusions), further restraining bank capital in the interim. For developers seeking new construction loans, many banks are aggressively pursuing or requiring their borrowers to open depository accounts and make deposits with the bank based on some percentage of the loan they want.

The ensuing market recalibration has quickly resulted in fewer, smaller, and more expensive construction loans. Whereas typical (nonrecourse) construction loan terms as recently as 15 months ago might have provided 65% loan-to-cost proceeds, most banks today are capping loan to costs at 50% unless the project sponsor provides some form of guarantees, personal recourse, or additional collateral. The lower senior loan proceeds are primarily driven by the higher interest rates and the assumption on resulting (lower) takeout financing proceeds. Consequently, developers have been forced to find additional capital to fill the void by raising additional equity or bridging the gap with either a mezzanine loan or preferred equity. Given the impact on existing high-volatility commercial real estate (HVCRE) bank regulations, most often this additional capital takes the form of preferred equity. The Fed’s HVCRE exposure regulations were implemented in 2015 as part of the new regulatory capital rules (Basel III), which effectively constrain bank lending on real estate development. Furthermore, because of deteriorating office and retail market conditions as well as existing portfolios’ exposure to these property types, apartment development (as well as warehouse or logistics projects) is the primary eligible asset class for construction financing. As shown in Exhibit 1, 72% of banks reported tightening lending standards to the Federal Reserve as of July 2023.

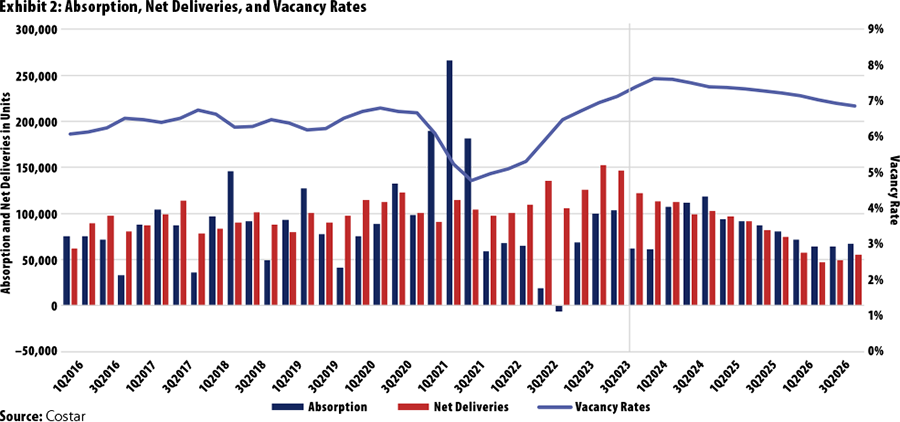

Fortunately, national apartment market fundamentals generally remain solid overall, with some reported softening in select markets that are facing abundant new deliveries. Occupancy, absorption, and rental rates continue to show positive statistics, as shown in Exhibit 2.

Capital Available for “Beds and Sheds”

Apartment and industrial remain the preferred asset classes still attracting capital. In addition to the overall favorable apartment market fundamentals, that sector remains a natural inflation hedge given the short-term nature of occupant leasing, which enables landlords to annually adjust rents to market. Additionally, re-tenanting costs are significantly less than in other real estate asset classes such as office and retail.

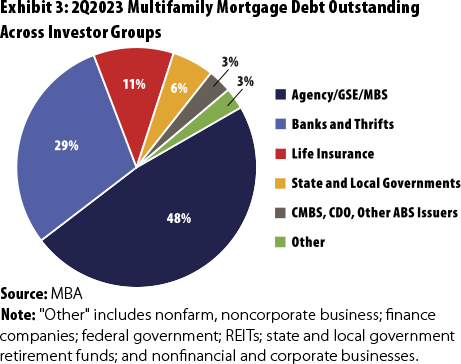

Overall investment capital, both debt and equity, is generally available given institutional demand for apartment assets as well as the unique support various federal government financing programs provide, including Veterans Affairs, the US Department of Housing and Urban Development, and Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac programs, which typically provide an estimated 50% of overall debt to the sector. The broad availability of debt financing from these federal programs is somewhat unique to the apartment sector, providing insulation from a liquidity crunch and enabling banks to underwrite reliable takeout financing not always available to other asset classes. However, banks remain the second largest debt source for the apartment sector, with a significant 29% share. Combined banks and GSAs provide a predominant 79% of debt capital to the apartment sector, which is evidence that other capital sources have ample opportunity to increase their exposure and potentially fill the void associated with the contraction in bank lending (Exhibit 3).

Lower Loan Proceeds Have Led to High Financing Costs

Construction financing costs have ballooned to levels not seen since the 1980s. For those select, predominately regional banks still cautiously lending for apartment development, the combination of rising interest rates and more conservative underwriting restricted by takeout loan assumptions has resulted in lower loan proceeds, typically capping out at 50% loan to cost, which has left a substantial void in the capital stack compared to more favorable conditions 12 to 15 months ago when loan proceeds generally hit 55% to 65% (depending on whether recourse was required). With typical bank spreads at SOFR +3.25%–3.50%, an overall senior loan interest rate of 8.57% to 8.82% results (assuming the current SOFR rate of 5.32%).

The resulting gap in proceeds and interest costs requires developers to either raise additional equity or fill the void with subordinate financing or some combination of both. Higher interest rates have led to higher construction loan pricing but have also reverberated up the capital stack in higher mezzanine loan and/or preferred equity and common equity pricing as well. With the cheapest part of the capital stack shrunken in size, coupled with the growth of more expensive gap financing, the total cost of third-party capital in a project’s cost has made it significantly more difficult for new projects to get capitalized.

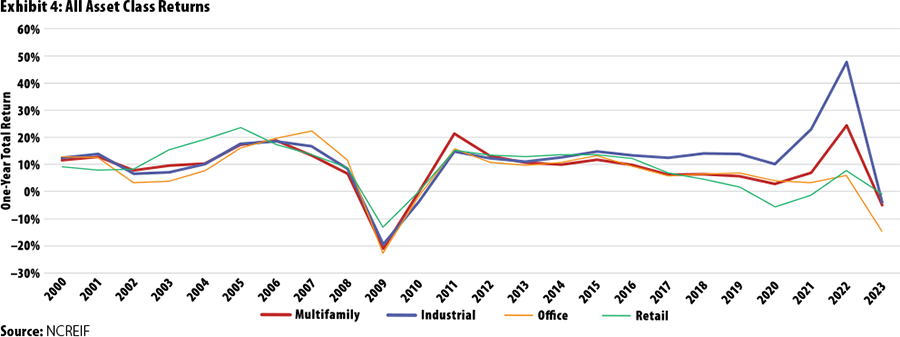

Higher interest rates have also influenced an expected rise in the cap rates investors require given the overall higher debt yields. As reported recently by NCREIF, investors in the past year required 20% higher overall returns for apartments. However, sellers have yet to concede, as evidenced by the decline of apartment sales activity. An expectation gap has constipated the sales market as sellers remain reluctant to sell, especially with market sentiment hoping for a reprieve of the Fed’s aggressive interest rate policy—although more recent market sentiment appears to anticipate higher rates for longer (Exhibit 4).

Structured Finance Sector Steps In

The resulting higher interest rate environment combined with noted banking constraints has created ideal market conditions for the structured finance sector that is willing and able to invest in apartment development projects. This sector is primarily made up of private, non-regulated investors that provide the entire debt stack in some cases or mezzanine and/or preferred equity in combination with a senior bank loan. These investors are able to generate significantly higher risk-adjusted returns because their attachment points are lower in the capital stack and the equity requirement subordinate to their investment is greater. For example, a typical preferred equity investment bridging the gap between a 50% loan-to-cost construction loan but capping out at 75% loan to cost would require subordinate equity equal to 25% of cost, thus providing a very robust equity cushion and a 1:1 ratio of common equity subordinated to the preferred equity. This key metric is quite favorable compared to years past when more typically experienced subordinate investors provided proceeds exceeding common equity.

Higher interest rates with more favorable investment parameters—specifically lower attachment and detachment points—equate to less risk as they fill a current market gap starting at 50% loan to cost and ending at 75%–80% loan to cost (typically). Similar terms a year ago would have had a starting attachment point of 60%–65% and a detachment point of +80%. With the surge in underlying interest rates, effective yields on this subordinate capital have increased to ranges of 14%–16%. Considering sponsors typically provide 20%–25% equity, these returns are quite attractive and have resulted in more capital entering the structured finance space. Consequently, common equity has become more difficult to obtain as higher-yielding returns on the subordinate debt and their commensurate risk profiles have become more attractive.

Necessity of Gap Financing

As bank construction loans have become increasingly more limited given their constrained capital, continued emphasis on the project sponsor and its internal capitalization is at the forefront. Sophisticated construction lenders have adapted to the evolving capital requirements and necessity for gap financing, which typically takes the form of primarily preferred equity, given bank requirements. Most banks prefer that gap financing be preferred equity versus mezzanine financing because mezzanine financing is generally construed as an additional loan—particularly if there is a pledge of collateral of the equity interest (note HVCRE requirements and thresholds). Preferred equity is more HVCRE friendly and is generally classified as senior priority to common equity although subordinate to the senior construction loan. Banks are loathe to provide preferred equity investors much in the way of notices or rights to cure because they overwhelmingly want to deal directly with the sponsor during construction and want to severely curtail rights and remedies to any class of preferred equity investors.

Structured finance platforms that have been successful in the space effectuate strong relationships with banks by working closely with them and emphasizing common interests. Of particular interest to most banks is the gap investor’s capabilities. Most mezzanine loans and/or preferred equity are primarily passive capital provided by investment funds with little or no development or operational capabilities. Consequently, banks are reluctant to provide them with either rights or notices other than when additional capital is necessary. Firms that can legitimately provide capital, development, and operational capability are viewed more favorably by the senior lenders because in the event of a default during construction, the subordinate lender can provide both mandated additional capital as well as problem-solving capabilities and the ability to complete construction and lease-up.

The constraints impacting traditional bank construction lenders are unlikely to abate anytime soon regardless of Fed policy. Bank regulators under pressure from the recent bank failures are more likely to increase regulatory supervision with an emphasis on higher bank capital requirements, which likely will lead to further bank consolidation. The apartment sector should remain a preferred asset class—demographics are favorable, market conditions are suitable, homeownership continues to be out of reach for most first-time buyers, and government agencies offer financing that is somewhat unique to the asset class. Given these solid fundamentals fueled by higher overall yields, expect new private and/or nonregulated entrants to fill the void of traditional banks, especially for apartment development.

Many life insurance companies seeking to diversify their real estate portfolios and reduce their office and retail exposure are considering providing construction financing.

Given the unique attributes and risk profiles associated with construction lending, many capital providers attracted to apartment fundamentals are constrained by their inability to provide and administer construction loans. These conditions along with the current banking environment have created a void for apartment developers.

Alternate Investment Sources

Many life insurance companies seeking to diversify their real estate portfolios and reduce their office and retail exposure are considering providing construction financing. However, life companies also operate with regulatory requirements that, similar to banks, require larger balance sheet reserves for riskier construction loans. Similarly, foreign capital providers are also likely to enter the market particularly because debt investments also have favorable tax considerations. Earlier this year, Canada-based Kennedy Wilson purchased a construction portfolio and team from Pacific Western Bank as part of the parent bank company’s recapitalization. Kennedy Wilson is already actively pursuing new apartment construction loans.

Significant additional investment opportunities will arise as bank apartment loans mature and are unable to fully refinance the underlying senior loan because of the gap resulting from higher interest rates. Construction risk will be eliminated because these completed projects will be in their initial lease-up phases, so more-diverse capital providers will be interested. Nonregulated private debt funds as well as more traditional investors will be attracted to these situations, offering interim bridge capital intended to provide ample time for sponsors to effectuate their business plans and ultimately get permanent financing at a later date, presumably in a more favorable interest rate environment.

Because these entities are less regulated, they retain more flexibility, and the underlying apartment fundamentals and demographics are enticing. Expect private debt funds to seek local operating partners to activate their programs. Construction lending is labor intensive and requires interdisciplinary organization and high levels of experience to mitigate the many hazards innate to the process.